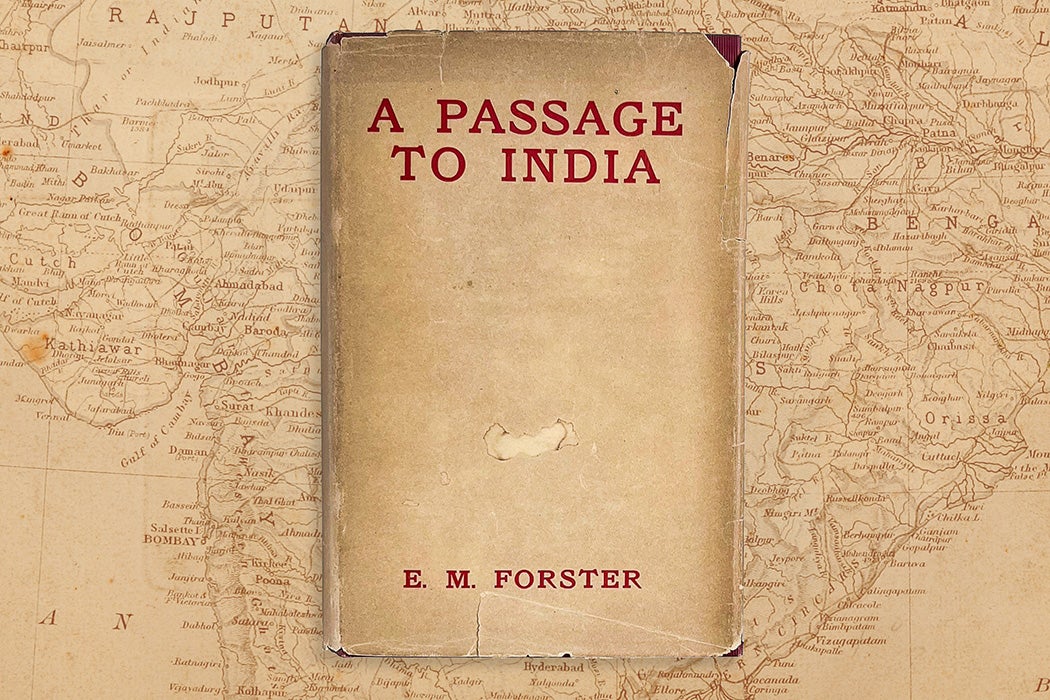

The period immediately following the Great War saw the rise of intense political activity in India. M. K. Gandhi, a lawyer who had just returned to his home country after spending twenty years in South Africa, was mobilizing the masses against the British government’s rule. Under his guidance, the Indian National Congress was working toward attaining self-governance for India—which later changed to a demand for complete independence. It was in this political and social backdrop that E. M. Forster wrote his novel A Passage to India.

Published in 1924, the book examines racial and cultural divides in the British empire in India through four characters—Dr. Aziz, a western-educated doctor from India; his British friend Cyril Fielding; and two British women, Mrs. Moore and Adela Quested. On a trip to the fictional Marabar Caves, Quested falsely believes that she is molested by Aziz. Despite no evidence to support her claim, the latter is subjected to an arduous trial, thus fueling racial tensions and prejudices between the natives and the British.

The book impacted the politics of the time by critiquing imperialist practices and subtly encouraging the Indian nationalist movement. Jeffrey Meyers, in his 1971 paper “The Politics of A Passage to India,” published in the Journal of Modern Literature, believes that Forster was “fully aware of the postwar political events that he wrote about during 1921–22 while living in India; and that he allude[d] to these events in his novel and use[d] them to enforce his political theme.” Meyers observes that the spirit of nationalism in India was strong during this period owing to the harsh treatment meted out to Indians by their British subjugators.

“Forster emphasizes the political implications of race relations, fear of riots, English justice and government, Hindu-Moslem unity, Indian Native States, nationalism and the independence movement,” explains Meyers. It’s evident that Forster’s sympathies lay with the Indian anti-imperialist cause, as he is known to have said the book “had some political influence—it caused people to think of the link between India and Britain and to doubt if that link was altogether of a healthy nature.”

Meyers also points out that Forster was keen to depict Indian nationalism, as with “Aziz’s assertion that there can be no self-respect without independence…” He rounds off his analysis by highlighting that the wrongful accusation of Aziz by Quested mirrors Britain’s wrongful assertion of India being “poor, backward, dirty, disorganized, uncivilized, promiscuous, uncontrollable, violent—in short, that she needs imperialism.”

Hunt Hawkins takes forward Forster’s critique of imperialism in A Passage to India in a 1983 paper published in the South Atlantic Review. However, he focuses on the idea of equality between races through friendship. “The central question of the novel is posed at the very beginning,” he writes, “when Mahmoud Ali and Hamidullah ask each other ‘whether or no it is possible to be friends with an Englishman.’ The answer, given by Forster himself on the last page, is ‘No, not yet…. No, not there.’”

Delving deeper, Hawkins observes the ironic situation that both parties find themselves in socially. Their predefined roles as oppressor and oppressed dictate their relationships. Hence, even those among them predisposed towards establishing friendly relations soon find themselves unable to do so.

Contemporaneous incidents in Amritsar, Punjab, such as the massacre of thousands of innocent protesters in a public park and the order for natives to crawl through a street where an Englishwoman was allegedly attacked, had caused a furor even amongst Western-educated Indians otherwise predisposed to look upon the British rule favorably. According to Hawkins, this led to a change of heart amongst Indians, represented by Aziz’s proclamation at the end of the book that “India shall be a nation! No foreigners of any sort! […] We shall drive every blasted Englishman into the sea, and then, and then, you and I shall be friends.”

Another socio-cultural phenomenon the book captures is the quest for Hindu-Muslim unity. Frances B. Singh stresses on this in her 1985 paper “A Passage to India, the National Movement, and Independence,” published in the journal Twentieth Century Literature. She highlights the need of young Muslims to seek out their own political identity, as distinct from the larger Hindu one. This is why Aziz, a Muslim character, says that “‘there is no such thing in existence as the general Indian,’ implying that for him Indian society is divided into two groups, Hindu and Muslim, each with own special interests and separate modes of perception.”

Weekly Newsletter

This differs from the political narrative encouraged by Gandhi, which was one of Hindu-Muslim unity. Singh shares that Gandhi’s “experiences in South Africa, where he had brought Indian Muslims and Hindus together, had convinced him that swaraj [self-rule] lay in the resolution of Hindu-Muslim tensions and the transformation of the relationship into one based on friendship and co-operation. Communal harmony, therefore, was associated with independence.”

The fact that Aziz chooses to settle in Mau, a Hindu-majority princely state that doesn’t fall under British rule, depicts Forster’s peculiar belief that the new Indian would be, “Muslim in sensibility, Hindu in political outlook.” And this, according to Singh, is “Forster’s implicit contribution to the national movement. It is a personal rendering of Gandhi’s idea of uniting Hindus and Muslims, a fictional counterpart to what Gandhi was trying to achieve through the medium of politics during the same period of time that A Passage to India was a work in progress.”

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.