Joseph Breintnall’s nature prints were made by inking both sides of a leaf and printing it between a folded sheet of paper, resulting in images of both sides of the leaf on the same sheet. In the 1730s and 1740s, these were an innovation in the study of American botany, writes art historian Jennifer L. Roberts, for they allowed “close empirical study of leaves but were more permanent and portable than real specimens.” Considering most botanists were on the other side of the Atlantic then, permanence and portability were key.

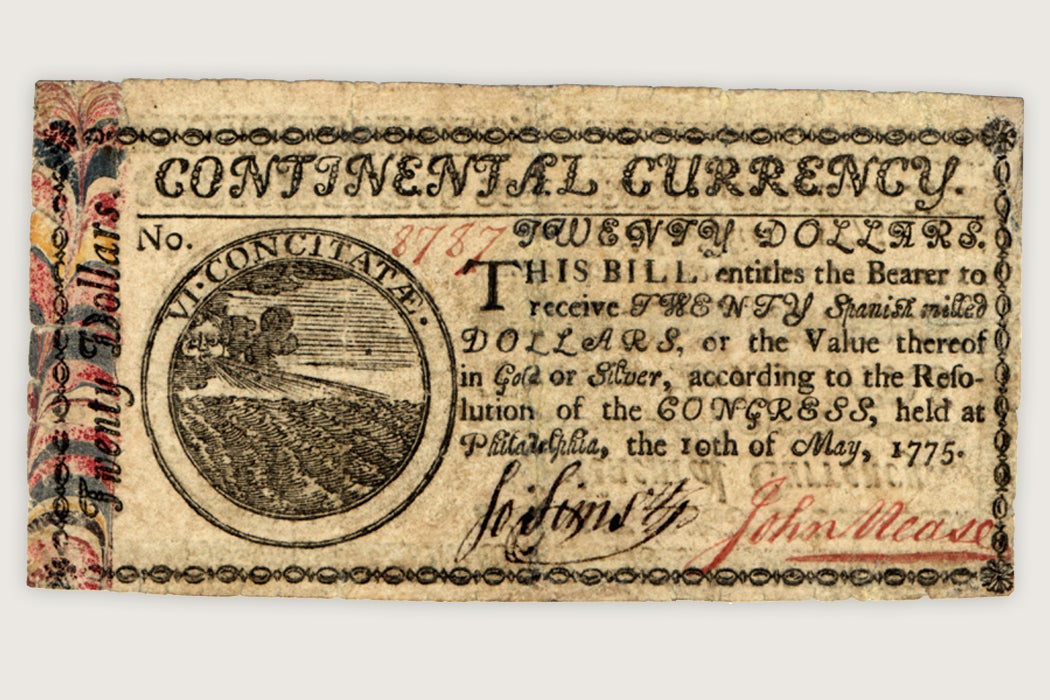

The prints were also an inspiration for Benjamin Franklin, a vigorous advocate of paper currency in the colonies. Franklin’s advocacy won him the legislature’s permission to print Pennsylvania’s money. Keenly aware of the unofficial competition, he used multiple methods to foil counterfeiters, including intentional misspellings and marbled paper. He also adopted Breintnall’s leaf prints, each one unique, into images for paper money. Some of the earliest American currency were thus “greenbacks” before their time, not because of their color but because they illustrated North American plants on their backs.

British merchants demanded payment in coin, but the British state was reluctant to export coins to the colonies. The result was a shortage of metal specie. As a result, “colonial America was site of some of the first and most extensive experiments with paper currency in the world,” explains Roberts.

But paper currency presented a big challenge. Franklin, like every currency designer, “had to confront a particularly difficult problem in the history of printing: how to create a print that could not be copied—how to create, that is, a nonreproducible reproduction. Each note had to be identical but also inimitable.”

More to Explore

Marbled Money

Breintnall and Franklin were both members of Philadelphia’s philosophical community. Breintnall was first secretary of the Library Company of Philadelphia, founded by Franklin in 1731 as the America’s first successful lending library, and a member of the Junto, Franklin’s conversation club. Franklin called him “very ingenious in little knicknackeries, & sensible conversation.” Besides his nature printing, Breintnall was “especially notable” for the letter he published in the Royal Society’s Transactions about his experience of being bitten by a rattlesnake.

In 1737, Breintnall wrote up a description of Rattle-Snake Herb for Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack, which had a circulation of about 10,000. The article includes an illustration, a direct leaf cast print. This print, writes Roberts, turns out to be a “momentous achievement in the history of printing, a watershed in print technology.”

“Franklin and Breintnall need a to find a way to transform the delicate venation of the leaf into a durable matrix that could be used to prints thousands of copies,” Roberts explains. “And they needed to do this without sacrificing the indexical immediacy of the nature print—without sacrificing the guarantee that the leaf had essentially printed itself.”

They did so by double-casting the leaf, essentially pioneering stereotyping—a “printing process that did not come into its own until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.” In stereotyping, the “original relief matrix is cast to create a paper or plaster mold, which is then cast again in metal […] ‘moving’ the original matrix into a more stable form for high-volume reproduction.”

Franklin used custom-formulated plaster (probably a “combination of asbestos, brick dust, and mica”) and typemetal to do it, and he realized that the resulting image was neigh impossible to forge by engraving. So, by August 1739, he was using the method on his currency. An early twenty-shilling bill featured three blackberry leaves.

Franklin taught the nature-printing process to select figures in Delaware, Maryland, and New Jersey, so nature-printed currency was found throughout the mid-Atlantic region. After Franklin went to Europe as a diplomat, David Hall and William Sellers continued his press’s production of currency, making nature-printed bills into the 1780s. Ultimately, “nature prints circulated on millions of pounds’ and dollars’ worth of paper currency.”

Weekly Newsletter

It wasn’t until 1963 that numismatists realized that Franklin’s and cohort’s bills were nature-printed rather than engraved. None of the blocks used to print them were known to be in existence.

“Early American type of any kind is extremely rare,” Roberts writes, because it was mostly recycled, melted down and recast. But in 2012, a block, “probably cast by Franklin’s successor Hall in 1760,” was found in the collection of the Delaware County Institute of Science in Media, Pennsylvania. It features three sage leaves.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.