From casual conversations to Supreme Court decisions, Americans often use our ideas about what the nation’s Founding Fathers believed to make sense of modern politics. And, as historian Jeffrey J. Malanson writes, that was already true at the time of the Civil War, less than forty years after Thomas Jefferson’s death.

If we know one line that Abraham Lincoln wrote, it’s probably the one about what “our fathers” did eighty-seven years earlier. And Malanson writes that this was no anomaly. Lincoln had studied the careers of Jefferson, George Washington, and other figures of the Early Republic from childhood and brought them up frequently in his speeches and writings. And so did his opponents.

Both supporters and opponents of slavery recruited Jefferson to their side. Abolitionists pointed to Jefferson’s rhetoric about the equality of men and his desire to see slavery eventually fade away. Spokesmen for the Slave Power, on the other hand, noted that Jefferson had enslaved 600 people and shown little interest in freeing any of them. Meanwhile, Washington was viewed both as the father of the unified nation and as a southerner, enslaver, and head of the convention that produced the slavery-endorsing Constitution.

Where northerners argued for the preservation of the Union created by the founders, Malanson writes, seceding states viewed themselves as heirs to the legacy of revolution in service of self-government and celebrated the Fourth of July in 1861 just as enthusiastically as the North. Some Democrats equated Revolution-era Tories with contemporary Republicans as “unconditional supporters of the government.”

And Lincoln’s frequent citation of the Declaration of Independence’s assertion that “all men are created equal” didn’t go unchallenged either. During their famous debates, Stephen Douglas argued that the concept of equality referenced in the Declaration of Independence applied to white men only. He noted that the founders were enslavers and asked whether that made them hypocrites. Malanson notes that, today, many observers would agree that they certainly were. But the nineteenth-century public held them in too high esteem to make that judgement. (For his part, Lincoln interpreted the famous phrase in a narrow way, claiming no political rights for Black Americans, only “natural rights” to escape enslavement and choose their own paths in life.)

Weekly Newsletter

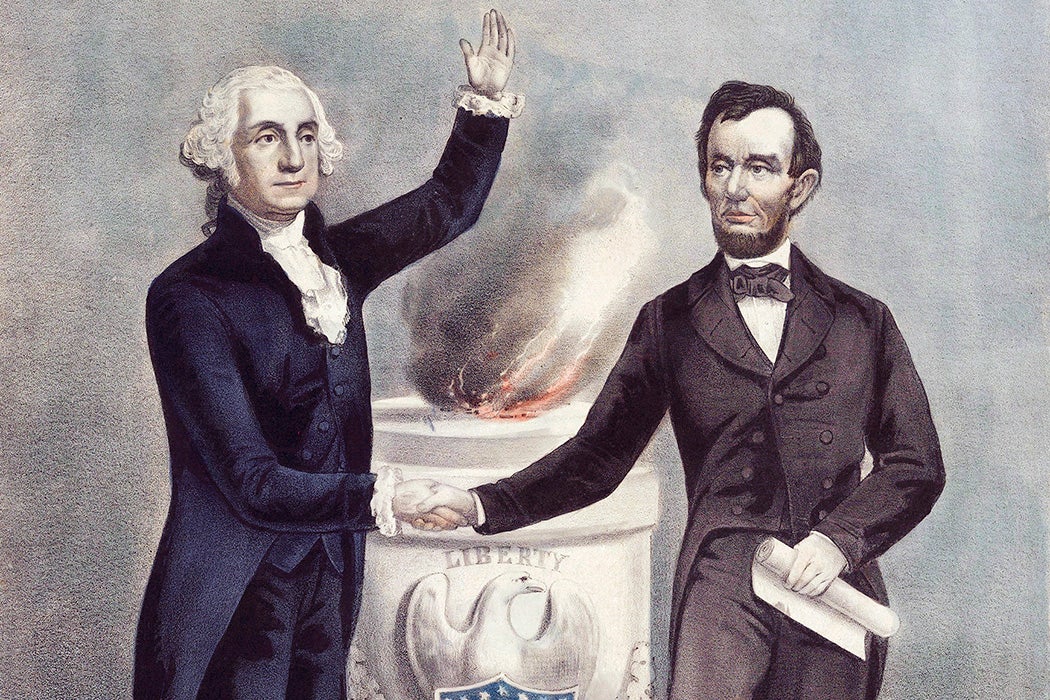

Some Republicans made direct analogies between the first president and the sixteenth—to the howling disdain of many detractors. One writer for a Connecticut Democratic newspaper called it “almost blasphemous” to compare the “Father of his country” with “the destroyer of a great people’s liberties, the foe of constitutional government, and the enemy of civil liberty.” Meanwhile, Democrats made their own attempts to link their candidate, George B. McClellan, with Washington. And the Confederacy chose Washington’s birthday in 1861 as inauguration day for Jefferson Davis.

Following the war’s end and Lincoln’s assassination, however, efforts to unite his legacy with Washington’s became commonplace, to the point that people united celebrations of their birthdays as Presidents’ Day (which, however, remains Washington’s Birthday in the eyes of the federal government).

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.