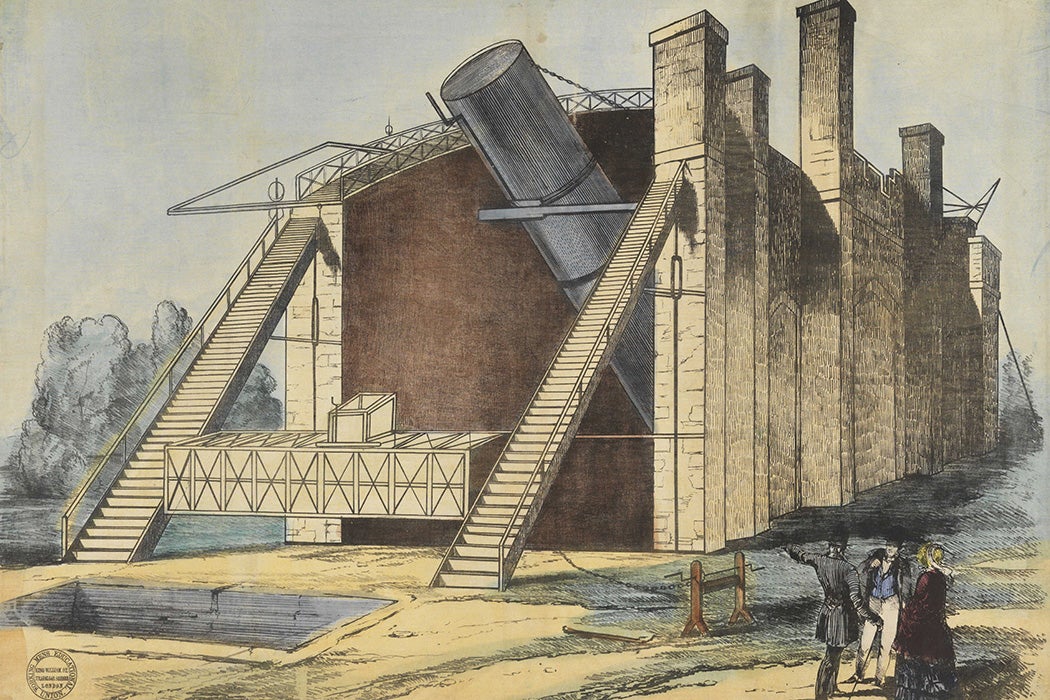

In 1845, near Birr Castle in Ireland, workers put the finishing touches on a gigantic telescope. Two massive walls rose around a fifty-five-foot wooden tube supported by wires. At the bottom of the tube, a six-foot-wide mirror awaited “first light.” This was the Leviathan of Parsonstown, the largest telescope in the world. Less than two months later, the team behind the Leviathan made a spectacular discovery.

They were at the cutting edge of astronomical research into nebulae. French astronomer Charles Messier had catalogued more than one hundred of these fuzzy splotches in the late seventeenth century, and then the Herschel family used large reflecting telescopes to find even more. Questions swirled around the nebulae–were they dense collections of distant stars, or large clouds of gas? William Parsons, third Earl of Rosse, built the Leviathan in part to help resolve these questions.

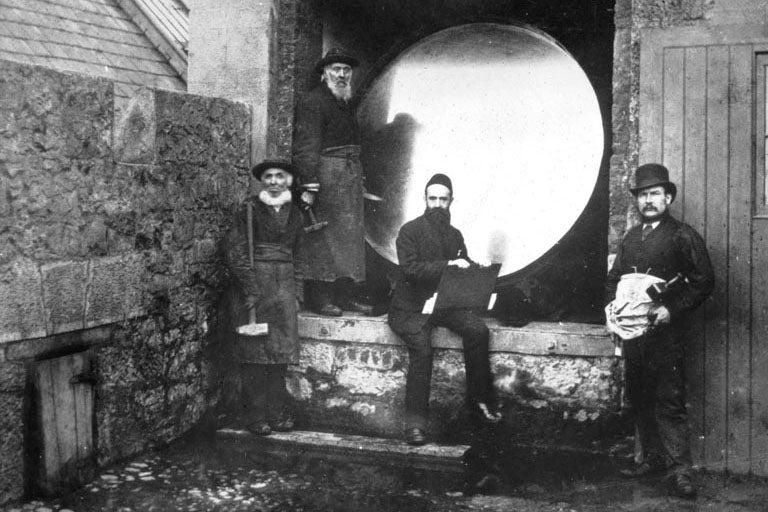

Science writer John Moore explains how Lord Rosse and his team tackled engineering puzzles in the process. They used a metal alloy called speculum for the mirror, which required finding a ratio of copper and tin that balanced strength with reflectivity. They also used innovative methods for casting and grinding the metal.

Wrangling the completed monstrosity required teamwork. Moore describes how observers stood on moving platforms while “instructions had to be shouted to helpers down below, who accordingly adjusted the pulleys to suit.”

In April 1845, the team pointed the telescope at Messier Object 51 (M51, a.k.a. the Whirlpool Galaxy) and saw something astounding. Where John Herschel had seen two rough circles, they saw a massive, elegant spiral. Rosse took a sketch to a meeting of British scientists that June—where Herschel was delighted by the revelation. Over the coming years, the Rosse project worked to produce more refined images of the spiral nebula.

Historian Omar Nasim describes Rosse and his assistants building these images over long periods. They sketched the nebula in parts, using an exacting procedure and numerous “working images.” Nasim argues that science and the sketching procedures were deeply entwined. Researchers “used an image to perceive an idea or conception of something,” he writes, “and to communicate and preserve that idea in the image.” Creating the image was part of figuring out exactly what the objects looked like, and what they were.

As astronomy further mechanized and photography proliferated, the Leviathan became less useful. In World War I, Moore writes, “nearly all of the iron castings and any other metal were melted down to contribute to the war effort.” But attempts to resurrect the Leviathan finally came to fruition in the late 1990s. Today, Birr Castle Demesne is once again home to a living and moving Leviathan.

Weekly Newsletter

Better tools did help solve the nebula puzzle. Some are star clusters, while others are masses of gas or dust—the remnants of dying stars or nurseries where new stars are born. Others still are entire galaxies, including M51. Today, M51 still captures the imaginations of amateur astronomers, many using miniature counterparts of the Leviathan that first revealed the great spiral.

Teaching Tips

- The Earl of Rosse, “Observations on the Nebulae. [Abstract],” Abstracts of the Papers Communicated to the Royal Society of London 5 (1843): 962–66.

- T. R. Robinson, “On Lord Rosse’s Telescope (Continued),” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1836–1869) 3 (1844): 114–33.

- “Lord Rosse’s Mammoth Telescope,” Scientific American 2, no. 10 (1846): 73–73.

- T. R. Robinson, “On Herschel’s Nebula, No. 44, as Seen in Lord Rosse’s Telescope,” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (1836-1869) 4 (1847): 236–37.

- “Visit to Lord Rosse’s Telescope,” Scientific American 3, no. 46 (1848): 363–363.

-

The Earl of Rosse, “Observations on the Nebulae,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 140 (1850): 499–514.

- “Lord Rosse, the Irish Mechanist,” Scientific American 10, no. 18 (1864): 282–83.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.