Born in West Virginia to parents who were sharecroppers, Ella P. Stewart was endowed with persistence and motivation in equal measure. She was the first Black female graduate of the University of Pittsburgh’s pharmacy school; the owner and operator—with her husband—of Toledo, Ohio’s first Black-owned pharmacy; and a formidable figure in the early movement for civil rights in the United States, serving as the president for the National Association of Colored Women, among other illustrious posts.

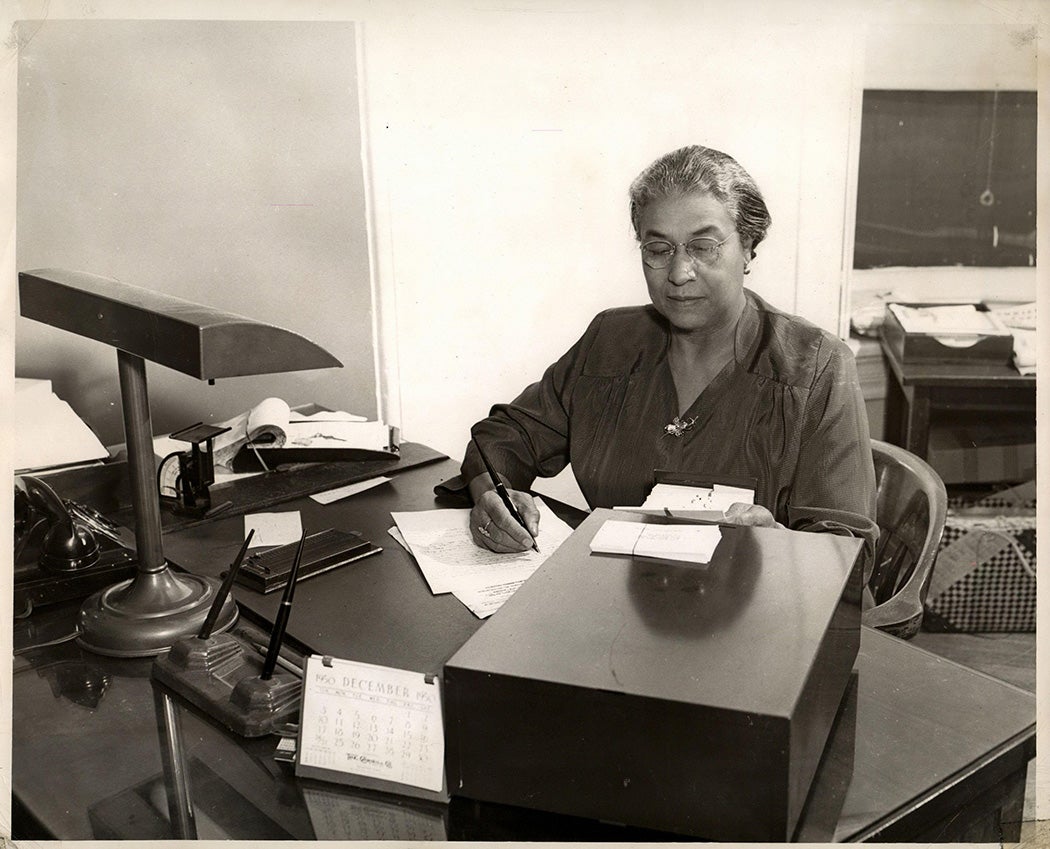

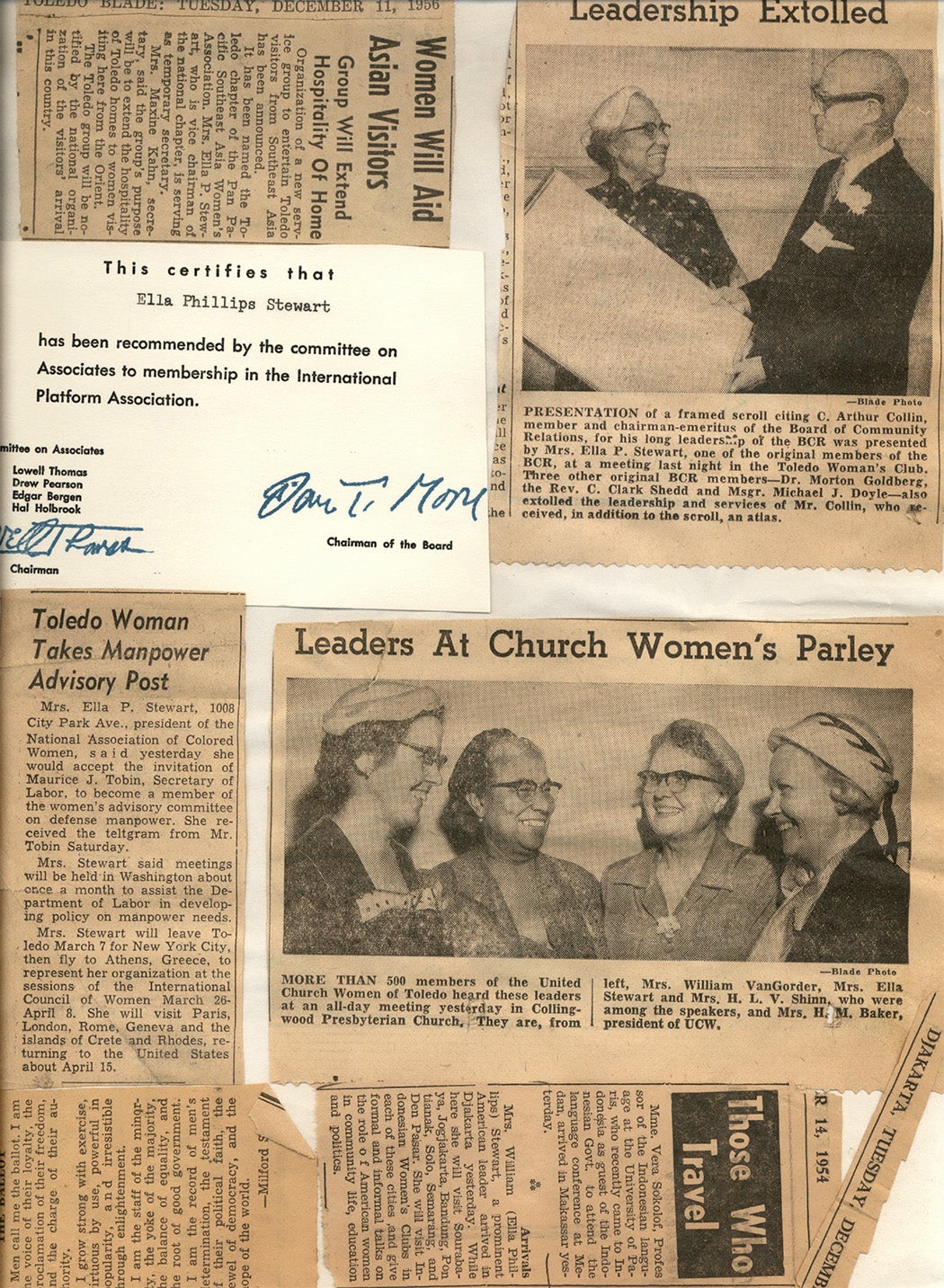

Stewart was also a prolific chronicler of her own story, keeping news clippings, photographs, and letters that span decades and continents. Together these items comprise the Ella P. Stewart Scrapbooks, now housed at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. The collection tell the stories both of a woman who triumphantly surmounted race- and gender-based barriers and of the pivotal role women’s political organizations played in paving the way for the Civil Rights Movement of the middle of the twentieth century.

Portions of the Stewart Scrapbooks have been digitized and are available to peruse as part of the collection Behind the Scenes of the Civil Rights Movements on Reveal Digital, JSTOR’s initiative to amplify important, long-overlooked voices of the twentieth century. Nick Pavlik, the digital archivist at BGSU’s Center for Archival Collections, spoke about Ella P. Stewart and the importance of her archive and legacy.

What can you tell us about Ella P. Stewart?

Ella P. Stewart’s pretty extraordinary. She was born in the 1890s, daughter of sharecroppers, grew up quite poor but was incredibly ambitious, very intelligent. She was accepted into Storer College in Harpers Ferry to become a teacher, and it did not take long after graduating to realize she did not want to be a teacher.

She was working as a bookkeeper at a pharmacy and ended up attending the University of Pittsburgh’s pharmacy school, from which she graduated in 1916. It was difficult for her to get accepted into the school because of discrimination, and she also faced a lot of discrimination while she was there, but she was one of the most determined, persistent people you would have ever met.

She wanted to open her own pharmacy, and it took a while to find the right location. She and her husband, William Doc Stewart, also a pharmacist who had graduated from the same school—traveled around working as pharmacists.

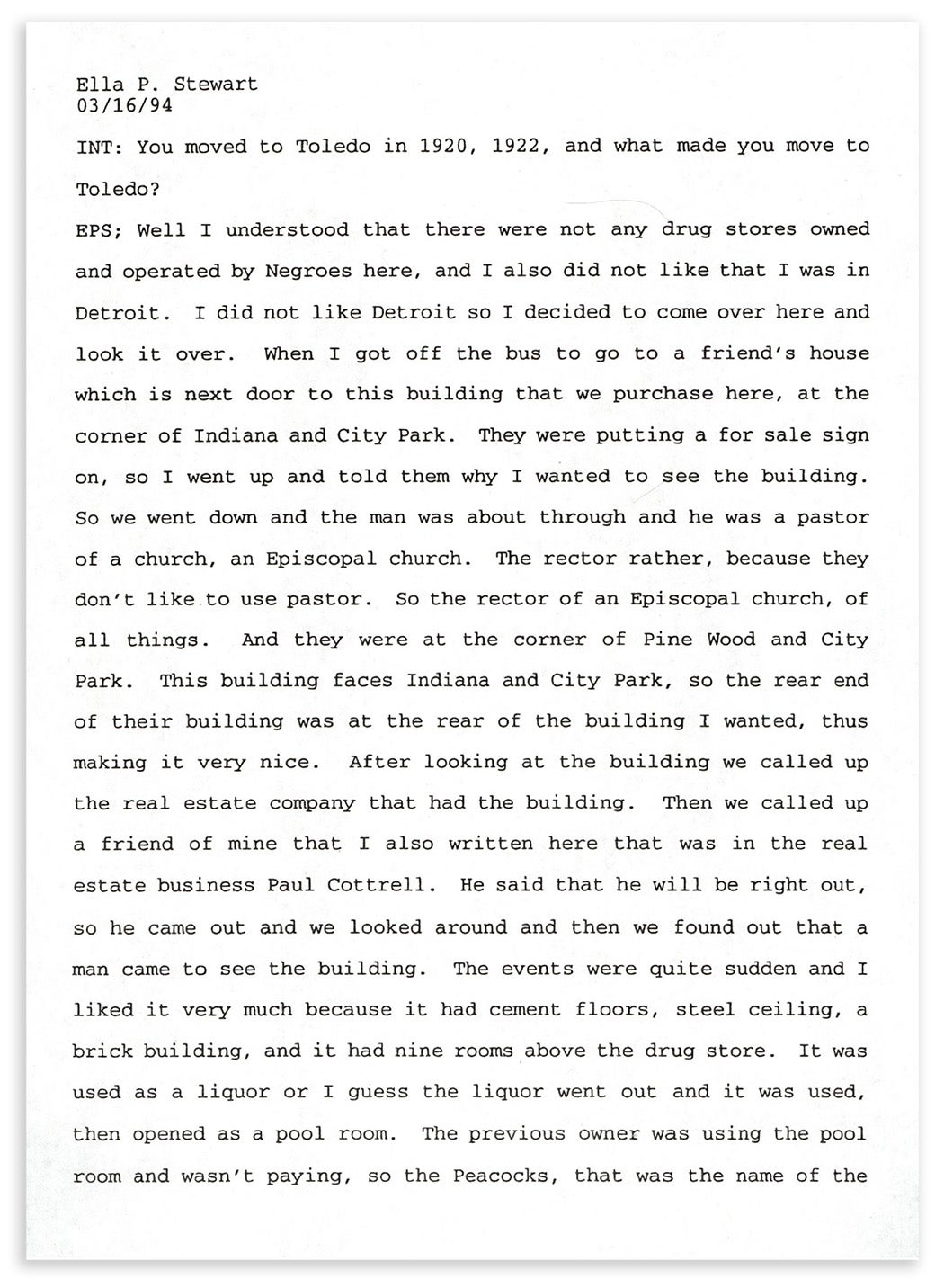

Eventually they landed in Detroit with the intention to establish their own pharmacy, but Stewart didn’t like Detroit, and they ended up coming down to Toledo when she learned that there were no Black-owned pharmacies there in the early 1920s.

They set up Stewart’s Pharmacy, which was in operation for the next twenty-five years. It was a pillar of the African American community in Toledo. Yes, it was a pharmacy, but it was also a community gathering place.

How so?

As Ella and Doc Stewart became pillars of the community, Stewart’s Pharmacy became one of those establishments that was a reliable haven for Toledo’s Black population. It was a place where everyone was welcome, and where the Stewarts knew all their customers personally. This was during the period before big chains, when local pharmacies felt much more reflective of the communities in which they were situated and were more than places you’d go to pick up your medications—they were important everyday social institutions. Stewart’s also sold household goods, snacks, and candy, and they had a soda fountain. It was the kind of place where customers dropped by just to “hang out.”

Ella and her husband lived in apartments right above the pharmacy, and their business was a sort of respite to the Black community. They housed Black luminaries who visited Toledo who were not allowed to stay at hotels due to discrimination. They would stay with Ella and Doc Stewart—people like W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Marian Anderson, Mary McLeod Bethune, Art Tatum, the jazz pianist who actually came out of Toledo.

In her oral history, Ella talks about how customers knew that if they ever needed anything after the pharmacy had closed, they could just ring her apartment, and she’d come down to help them. Stewart also had white clientele, so Stewart’s was somewhat integrated during a time when that was not at all common in Toledo, or anywhere else in the US for that matter. I think Black residents were comfortable with that because they knew the Stewarts would have zero tolerance for racist behavior from white customers. And while Ella P. Stewart was a pharmacist, she also started to get involved in civil rights activism, civil rights work, and community organizing.

What was the nature of her activism?

One of the first charities that she began working with was called the Enterprise Charity Club. That was an organization led by Black women, intended to help Black families coming up to Toledo from the South. This was peak Great Migration era, and so for families from the rural South, you can imagine kind of what a culture shock that was for them—a lot of adjusting. The Enterprise Charity Club helped those families get settled. They would provide them with household goods, materials, anything that they might need to help get themselves situated upon arriving.

Ella P. Stewart became recognized locally as a leader and ended up president of the Ohio Association of Colored Women, and from there was appointed president from 1948 to 1952 of the National Association of Colored Women, also called the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs. During her presidency, they lobbied for passage of anti-lynching and anti-poll tax legislation, fair employment practices, equal opportunity for housing and education, support of Black-owned businesses, and the development and expansion of endowment and scholarship funds for young Black women.

What more do we know about these associations and clubs?

They existed because there were so few resources for Black people in the first half of the twentieth century. Limited access to educational opportunities, professional opportunities, you know—wealth gaps, disparities, living conditions—and there were very limited public institutions set up to provide support for people of color during that time.

Black women’s clubs took it upon themselves to raise the money and provide the resources to people of color and other marginalized communities simply to have the opportunity to have a quality of life comparable to the white population.

For Stewart, that was the focus of her of her life’s work. She and her husband did very well as pharmacists, and once they were able to retire, in the mid 1940s, she was able to just focus on civil rights work exclusively.

What was the specific nature of the discrimination she faced in pharmacy school?

She had to sit in the back. She was the only Black student there, excluded from the rest of the students. She would receive secondary second-rate materials, books, other supplies, just did not have the kind of access to needed resources that other students had.

Two remarkable things about her stand out to me: her pioneering effort in breaking color barriers and her great empathy for others.

Absolutely. After her presidency for the National Association of Colored Women, she focused on local civic matters in Toledo in the 1950s and1960s, becoming involved with the Toledo League of Women Voters, the League of City Mothers, Toledo Council of Churches, the Young Women’s Christian Association, and the Toledo Board of Community Relations, which was an organization that had been set up in the 1960s to address racial inequality.

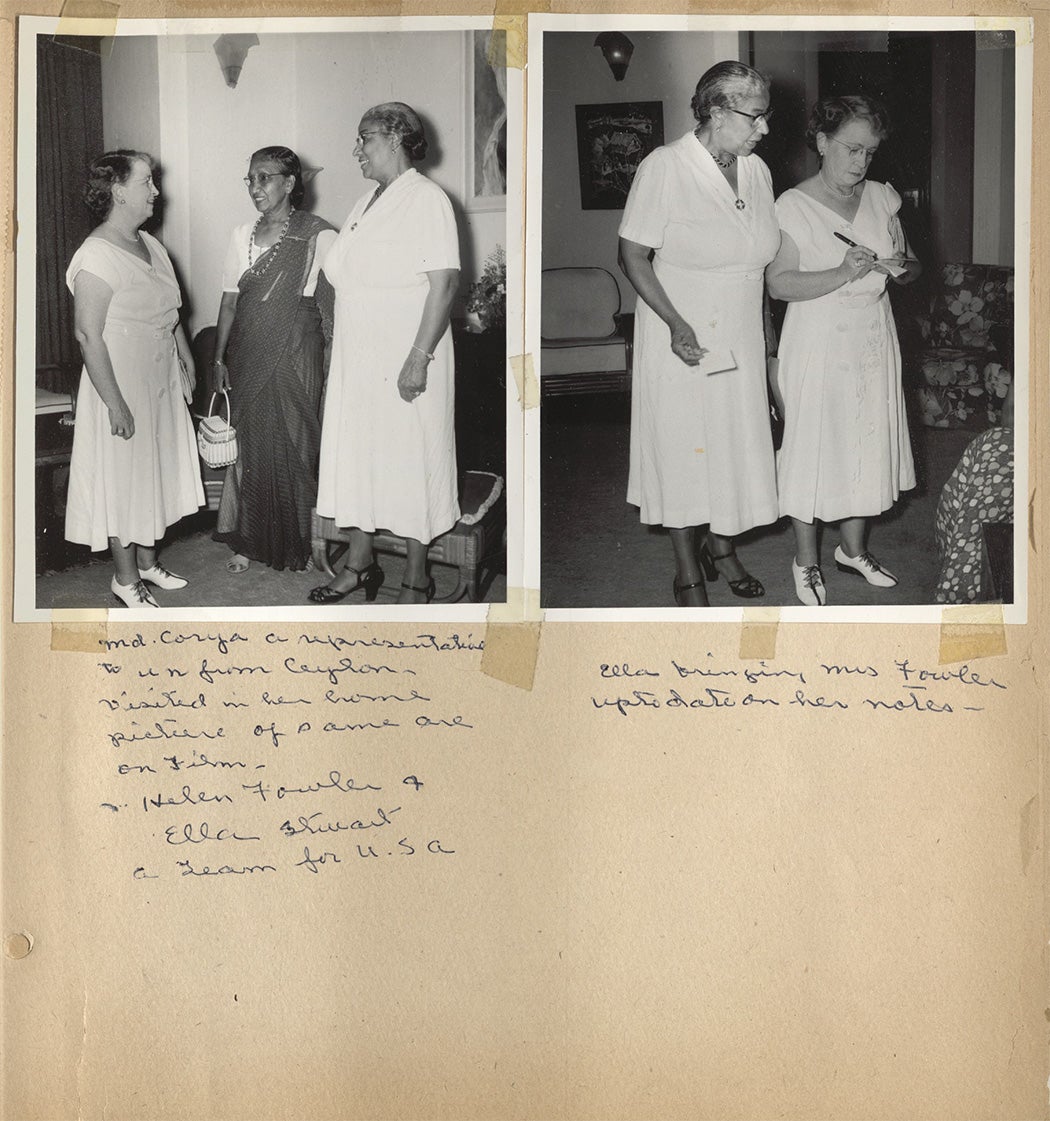

As a member of those organizations, she worked to desegregate certain institutions. She had a hand in desegregating nursing schools in the Northwest Ohio region and allowing Black girls to be admitted to the YWCA in Toledo. She was a dogged activist on behalf of Black people across the country, locally, throughout the world. She was warm and charming, someone who was at ease wherever she went, and never allowed the discrimination and persecution she faced to detract from what she was motivated to accomplish. She had such a great ability to win people over. And a lot of what she accomplished, she did through development of personal relationships with people in positions of power who were able to then enact change.

What specifically can we find in the scrapbooks?

The materials pretty much span the entirety of her life from the time that she went to pharmacy school all the way up to her death and beyond, as there are

materials collected after—commemorative articles written about after her death.

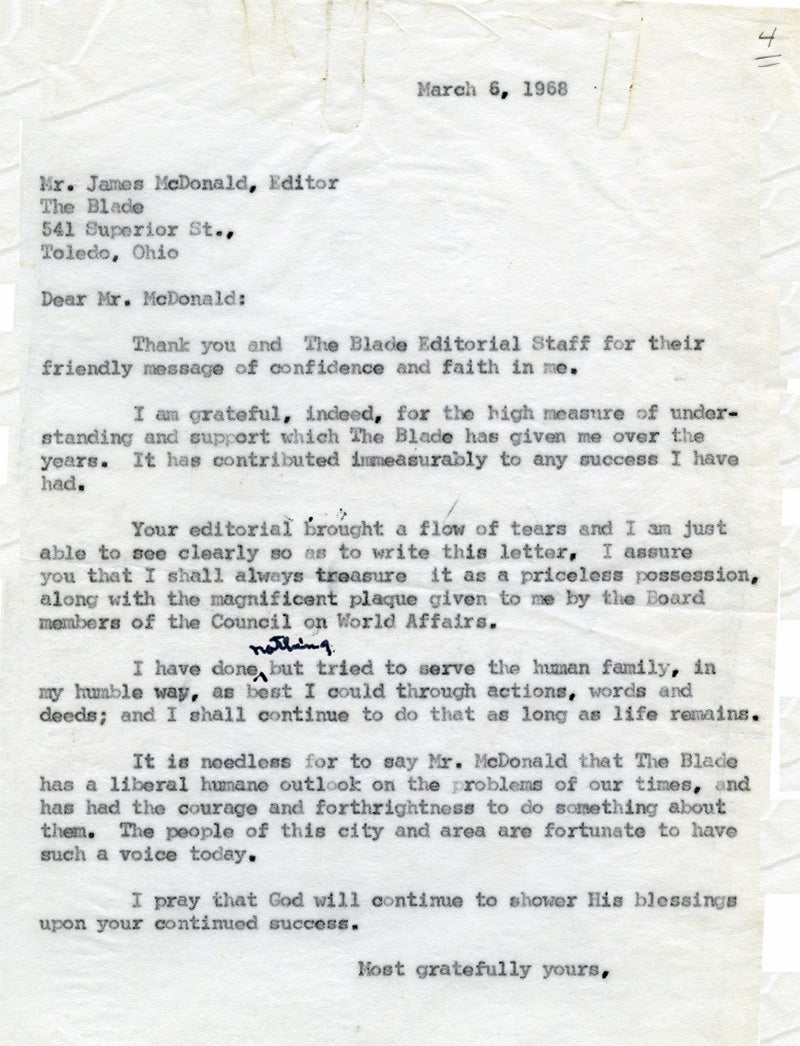

It’s a lot of letters between Ella and various figures, friends, extensive photographs, clippings as well. She was a prolific newspaper clipper, and she would jot down notes next to the article, mostly pertaining to issues of race, discrimination, politics, local civic matters.

All kinds of materials from the organizations that she was part of, so printed programs, organizational records, annual meeting, minutes, the things that document the work that she did as a member of those organizations.

There’s an oral history recording as well recorded in 1980s, a few years before her death; the archivists here at the Center for Archival Collections (CAC) recorded that (transcribed in 1994), and that’s a wonderful resource where you can get a sense of what she was like as a person.

What items in the collection surprised you?

The photographs from her presidency with the National Association of Colored Women give an amazing glimpse of the behind-the-scenes work of that association. Also, the scrapbooks that she kept from her time as a goodwill ambassador to the United Nations, traveling the world as a Representative of the US to advocate for marginalized people. She went to Greece, India, Southeast Asia, Turkey. The scrapbooks from those trips are intact, and those photos are much more candid; you get the sense of the confidence that she had, and how she was at ease no matter what situation or environment. You can tell how respected she was, how natural a leader she was from looking at her interacting with members of varying cultures throughout the world. There’s such a rapport that she’s able to quickly establish, and that was the power that she had as an activist.

How did this collection land at Bowling Green State University?

Great question. We’ve wondered that as well. In the 1980s, we had a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to undertake a collecting initiative aimed at acquiring better archival documentation of Northwest Ohio women’s history. This was during a time when we were bringing in several collections, a lot of women’s clubs, individual women who had been involved in various organizations, or simply women who did not have anything notable, so to speak, that they accomplished, but their personal papers or their diaries provide credible glimpses into the everyday life of women in Northwest Ohio from the nineteenth through the mid-twentieth century.

Weekly Newsletter

Now there was a very prominent figure in Toledo, a labor lawyer and community activist in his own right—Edward Lamb. He was a good friend of Ella P. Stewart’s, and when we started to undertake this women’s history collecting initiative, he helped put us in touch with her. She was a prolific documenter of her own life because she knew, not in any kind of self-aggrandizing sense, that what she had accomplished and what she had lived was quite extraordinary. So, she was thrilled when we contacted her. She had amassed these scrapbooks that were an incredible document of those accomplishments as well as the history of civil rights in twentieth century United States.

What lessons can we glean from her life and career about the larger struggle for social justice?

We all know about the civil rights movement of the 1960s, but much less is known about the foundations that that led up to that. And that’s what this collection is all about—the work that was done primarily by Black women through the structure of Black women’s clubs to work towards civil rights for all Black people in the in the US, and through charitable organizations, advocacy organizations, working to desegregate facilities and institutions, providing scholarships and working for education rights for Black children—all of that work that led up to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, you know, all of the foundations for that were of course laid earlier in the century, and, and Ella P. Stewart was a pivotal figure who helped lay those foundations. The National Association of Colored Women of course is a very important organization in the earlier history of civil rights in the United States and a testament to the importance of the role Black women played in civil rights activism.

That’s really what makes this such a gem of a collection; it relates to an aspect of the civil rights movement that that gets less attention in the public imagination but is no less important. All those people who were pioneering leaders of the civil rights movement of the sixties—they were inheriting a tradition that had been laid down earlier in the century by Black women activists.

Support JSTOR Daily! Join our membership program on Patreon today.